Recent Content:

I grew up on the fringes of suburbia, at the cusp of what most would consider rural Pennsylvania. In the Spring, we gagged from the stench of manure. In the Fall, Schools closed on the first day of hunting season. In the Winter, fresh, out-of-season fruits were missing from the grocer. All year round, procuring exotic ingredients like avocados entailed a forty-five-minute drive toward civilization. During the school year, I was the first to be picked up and last to be dropped off by the bus, enduring a ride that was well over an hour each way.

I also grew up in tandem with the burgeoning cruise line industry. My parents quickly adopted that mode of travel, and it eventually became our sole form of vacation. As a kid, it was great: I had the freedom to roam the decks on my own, there were innumerable activities, and an unlimited supply of delicious foods with exotic names like “Consommé Madrilene” and “Contrefilet of Prime Beef Périgueux”. My parents loved it because it kept their kids busy, was very affordable (relative to equivalent landed resorts), and had sufficient calories to satisfy their growing boy’s voracious appetite. This was also a transitional period when cruises were holding onto the vestiges and traditions of luxury ocean liners. All cruise lines had strict dress codes, requiring formal attire some evenings (people brought tuxedos!). The crew were largely Southern and Eastern European. As a kid who had never traveled outside North America, it felt like I was LARPing as James Bond.

When I moved out of my parents’ house for college, I wanted a change of scenery. While I had the option to move to a “college town”, I instead chose to live in a large city. And I loved it. It was like living on a cruise, all year round: Activities galore, amazing food, and all within a short distance of each other. A friend could call me up and say, “Hey, we are hanging out at [X], would you like to join us?” And, regardless of where X was in the city, I could meet them there within fifteen minutes either by walking, biking, or taking public transport.

I didn’t need cruises anymore.

Preface

This year, for his birthday, my father only had one request: that he and his extended family take a cruise to celebrate. I just returned from that cruise, and it was a very different experience from the ones of my youth.

As an adult who had by this point lived the majority of his life in large cities, all I wanted to do was lay by a pool or, preferably, the beach all day and read a book. Those are both difficult things when you’re sharing a crowded pool space with over six thousand other people, and the ship doesn’t typically dock close to a good beach. Skating rink? Gimmicky specialty restaurants? Luxury shopping spree? Laser tag? Pub trivia? Theater productions? Comedy shows? I can do all of those things any day of the week a short distance from my house. When I vacation, I want to escape all that freneticism.

My wife, kids, and I were the only urbanites in our group, and my parents didn’t seem to comprehend why we had such little interest in all the activities. And then it dawned on me: A cruise is just a simulated city. Why would I want an artificial version of what I already have?

So, lying down on a deck chair, instead of reading my book, I started writing. The idea of simulated urbanism isn’t new, but it’s typically discussed in terms of curated amusement parks like Disney and the emergence of suburban “lifestyle center” developments. Therefore, initially, my goal was to channel this insight into as obnoxious a treatise as possible, in order to trigger my suburbanite traveling companions. Simulated urbanism? That reminded me of Baudrillard! I would make it a completely over-the-top academic analysis of the topic.

The following was compiled from a series of texts I sent to our group chat throughout the cruise.

Abstract

This article explores the paradox of vacation preferences among suburban Americans who gravitate toward densely populated environments such as cruises, European cities, and amusement parks, despite residing in sparsely populated areas. It examines how cruises and lifestyle centers, which mimic urban density while offering suburban convenience, satisfy the suburban desire for urban-like experiences. The article contrasts these preferences with those of urban Americans, who experience density daily and may seek different vacation experiences. By analyzing the dynamics of suburban and urban vacation choices, we highlight the complex interplay between suburban living and the pursuit of urban escapism.

Simulated Urbanism

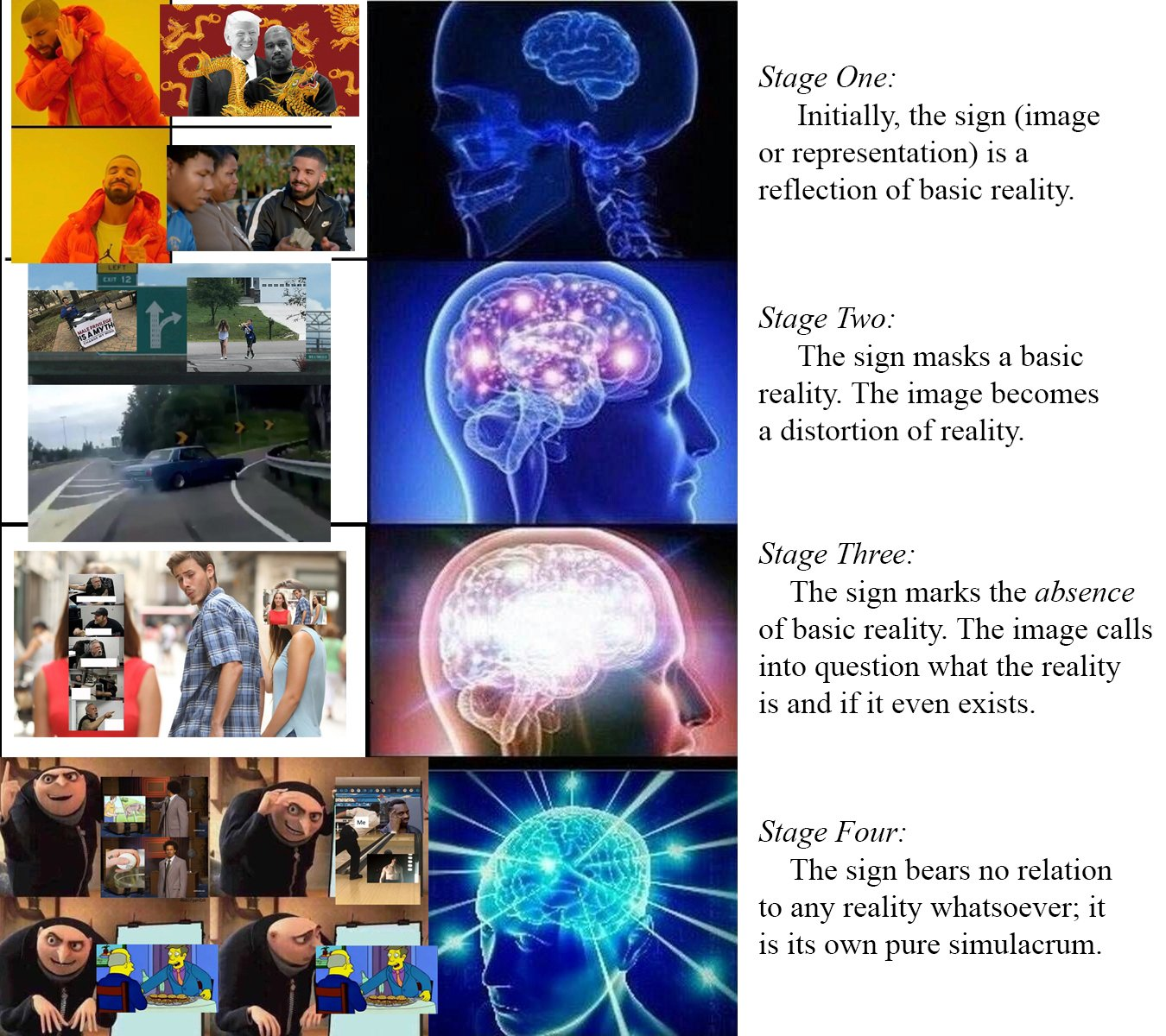

Simulacra and Simulation

The concept of “simulated urbanism,” as seen in cruise ships and lifestyle centers, can be analyzed through the lens of Jean Baudrillard’s philosophy, particularly his ideas on simulation and hyperreality. Baudrillard argues that in contemporary society, simulations—representations or imitations of reality—have become so pervasive that they blur the distinction between what is real and what is artificially constructed. In the context of simulated urbanism, lifestyle centers and cruise ships serve as hyperreal environments that imitate the vibrancy and density of urban life without the complexities and inconveniences associated with real urban spaces. They provide an experience that is more accessible, manageable, and, in some ways, more appealing than the genuine urban environments they emulate. According to Baudrillard, these simulations can create a sense of hyperreality, where the imitation becomes more influential or desirable than reality itself. Suburban Americans, who are accustomed to the sprawling, car-dependent landscapes of suburbia, find in these simulated urban environments a curated and sanitized version of city life. This artificial urbanism allows them to engage with the aesthetics and experiences of urban density—such as walkability, diverse entertainment, and social interaction—without the perceived drawbacks of real urban living, like congestion, pollution, and crime. Thus, simulated urbanism not only fulfills a desire for the excitement and dynamism of city life but also constructs a hyperreal experience that is tailored to the preferences and comfort of suburban consumers, aligning with Baudrillard’s notion of a society increasingly detached from the authenticity of the real world.Metamodernism

Suburbanites’ predilections for cruising can be interpreted through the theoretical framework of metamodernism, which posits an oscillation between opposing cultural and experiential paradigms. The cruise experience encapsulates a synthesis of modernist aspirations for progress, order, and structured entertainment, alongside a postmodern sensibility characterized by irony and skepticism towards mass consumerism and the spectacle. This dialectical tension aligns with metamodernism’s core principle of navigating and reconciling contradictions. Within the confines of a cruise, suburbanites engage with the modernist ideal of escape and luxury, encountering a curated simulacrum that offers both adventure and novelty. Simultaneously, they remain cognizant of the inherent artifice and commodification intrinsic to the cruise experience, reflecting a postmodern consciousness of the limitations and constructed nature of such escapism.

Furthermore, the pragmatic idealism inherent in metamodernism is evident in the suburban pursuit of cruising, representing a quest for authenticity within a meticulously orchestrated environment. Suburbanites partake in cruising as a form of meaningful escapism that, although commodified, facilitates genuine opportunities for relaxation, social interaction, and cultural exploration. This dynamic reflects a metamodern synthesis of sincerity and irony, wherein participants seek genuine engagement and fulfillment while maintaining an awareness of the artificial and consumerist underpinnings of the cruise industry. The cruise, thus, serves as a microcosm of metamodern cultural hybridity, integrating diverse influences and experiences into a cohesive assemblage that enables suburbanites to navigate the complexities of contemporary existence with both optimism and reflexivity. This exemplifies the metamodern tension between the yearning for authentic connection and the recognition of its mediated nature, embodying a dialectical interplay that is central to metamodern thought.

Dialectics

(To be read as if dictated by Slavoj Žižek.)

From a Hegelian perspective, urbanites’ preferences for relaxing vacations can be understood through the lens of dialectical progression and the quest for synthesis between opposing elements in their lives. Hegel’s philosophy emphasizes the process of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, [sniff] where the contradictions and tensions between different aspects of existence lead to the development of higher levels of understanding and being. A dance of contradictions and tensions.

Urbanites are like rats in a maze of their own making, living in this frenetic environment of constant stimulation and complexity. So, what do they do? They escape to a vacation that provides the antithesis of urban life, a necessary counterbalance that allows them to confront the contradictions of their daily existence.

In this dialectical process, the vacation can be seen as a moment of synthesis, where urbanites integrate the contrasting aspects of their existence—work and leisure, complexity and simplicity, stimulation and relaxation. Through this synthesis, they achieve a more harmonious state of being, temporarily resolving the contradictions inherent in their lives. [nose pull] Hegel might argue that this pursuit of balance is part of a broader process of self-realization and development, as individuals continually seek to reconcile opposing forces within themselves and their environments. This dialectical movement reflects a deeper philosophical journey toward self-awareness and fulfillment, where each vacation experience contributes to a more nuanced understanding of personal and existential needs.

Moreover, Hegel would likely emphasize that this process is not static but dynamic, as urbanites constantly redefine and re-evaluate their desires and experiences in pursuit of higher forms of understanding and contentment. [sniff] This ongoing dialectical interaction between urban life and vacation preferences underscores the complexity of human existence and the continuous evolution of individual consciousness within the broader historical and cultural context.

What Would Marx Say?

(For extra fun, to be read as if dictated by Jordan Peterson.)

When we examine the suburbanite’s preference for urban-like vacation experiences—such as cruising or visiting bustling cities—through the lens of Marxist theory, we uncover something quite profound about the alienation inherent in capitalist societies. Suburban life is often marked by routine and compartmentalization, a strong reliance on cars, and an emphasis on private space. This creates an environment of isolation and fragmentation, which Marx identified as symptomatic of capitalist production. The sprawling nature of suburbia physically separates individuals from their workplaces, social hubs, and cultural activities, generating a dichotomy between home life and community engagement. This alienation from collective social experiences mirrors the detachment workers feel from the products of their labor and from each other in a capitalist framework.

Thus, when suburbanites seek out vacations in dense, walkable environments, they’re searching for a temporary reprieve from this isolation. These vacations allow them to engage with the social interactions and cultural experiences that are often missing from their everyday lives. In this way, vacations become a commodified form of leisure within capitalist society, packaged and sold as products designed to alleviate the stresses of alienation and labor. Suburbanites, who feel the pressures of maintaining a lifestyle dictated by capitalist norms—like homeownership and consumerism—turn to vacations as a form of respite from these demands. Cruises and urban vacations offer a concentrated form of entertainment and cultural engagement, providing an illusion of freedom and choice that contrasts with the regulated and constrained nature of suburban life. While these vacations temporarily satisfy the need for genuine human connection and cultural enrichment, Marxist theory would argue that they also reinforce the capitalist cycle, as individuals must return to their suburban routines to earn the means to participate in such leisure activities. Thus, vacations, though they offer a brief escape from alienation, ultimately underscore the pervasive influence of capitalism on leisure and personal fulfillment.

Conclusions

As I reflect on the whirlwind of contradictions, philosophies, and cultural dynamics explored in this article, I must admit that I find myself utterly exhausted. Much like the aftermath of a cruise, where the buffet line feels both endless and insurmountable, I am too fatigued to draw any tidy conclusions. So, dear reader, as I lean back in my metaphorical deck chair, I invite you to navigate these intellectual waters and draw your own conclusions. Like the towel animals on your cabin bed, reality might be folded and shaped in surprising ways, but the essence remains yours to unravel. Bon voyage in your own journey of trolling! Or is it trawling?

How to avoid the aCropalypse

It could have been prevented if only Google and Microsoft used our tools!

Last week, news about CVE-2023-21036, nicknamed the “aCropalypse,” spread across Twitter and other media, and my colleague Henrik Brodin quickly realized that the underlying flaw could be detected by our tool, PolyTracker. Coincidentally, Henrik Brodin, Marek Surovič, and I wrote a paper that describes this class of bugs, defines a novel approach for detecting them, and introduces our implementation and tooling. It will appear at this year’s workshop on Language-Theoretic Security (LangSec) at the IEEE Security and Privacy Symposium.

The remainder of this blog post describes the bug and how it could have been detected or even prevented using our tools.

A couple of years ago I released PolyFile: a utility to identify and map the semantic structure of files, including polyglots, chimeras, and schizophrenic files. It’s a bit like file, binwalk, and Kaitai Struct all rolled into one. PolyFile initially used the TRiD definition database for file identification. However, this database was both too slow and prone to misclassification, so we decided to switch to libmagic, the ubiquitous library behind the file command.

I am proud to announce the release of it-depends, an open-source tool for automatic enumeration of dependencies. You simply point it to a source code repository, and it will build a graph with the required dependencies. It-depends currently supports cargo, npm, pip, go, CMake, and autotools codebases, packages in their associated package managers, and Ubuntu apt.

I recently created a challenge for the justCTF competition titled PDF is broken, and so is this file. It demonstrates some of the PDF file format’s idiosyncrasies in a bit of an unusual steganographic puzzle. CTF challenges that amount to finding a steganographic needle in a haystack are rarely enlightening, let alone enjoyable. LiveOverflow recently had an excellent video on file format tricks and concludes with a similar sentiment. Therefore, I designed this challenge to teach justCTF participants some PDF tricks and how some of the open source tools I’ve helped develop can make easy work of these forensic challenges.

Read the full post on the Trail of Bits blog for spoilers on how to solve the puzzle.

Note: My advice is specifically related to the higher education system in the US; other countries have very different systems. My advice is also solely based on experience in the field of Computer Science; this may translate to other STEM fields, but certainly not all academic fields.

Do you really want a Ph.D.?

Make sure you are doing this for the right reasons!

Reasons to get a Ph.D.

- You want to work in academia. If you want to get a tenure track research position at a university, you need a Ph.D.

- You need it to get a promotion at work. This is typically only true at larger corporations, where having certain credentials is necessary to progress through the ranks.

- You enjoy being in an academic environment and solely want the experience. This is perfectly valid. Being in grad school can (but isn’t guaranteed to) be incredibly invigorating.

Reasons not to get a Ph.D.

Dat Phizzle Dizzle Doh

The novelty of putting those letters after your name and/or being called “Doctor” wears off real quick.You just want to teach at a university

Universities are really hungry for adjunct professors these days. You usually don’t need a Ph.D. to teach. Try teaching a class or two before you commit to getting a Ph.D. and making that your career. I’ve taught a bunch of classes, both at the undergraduate and graduate levels, including developing the entire syllabus, assignments, and slides all from scratch. It is a lot of work, and usually not worth what they pay you.You want to work on your dissertation topic for the rest of your career

I know dozens, maybe hundreds of Ph.D.s, and I can count on one hand the number of people who continued research related to their dissertation topic after graduation.Imposter Syndrome

I’ve worked with plenty of people with no degree who are far more capable than people with multiple grad degrees.You’re probably not going to get a job in academia

I know several people who got Ph.D.s from top tier schools like CMU and MIT and all of them either ended up in industry or teaching at small liberal arts schools with no graduate program (because they were dead set on ascending the ivory tower). The academic market is super tough, and will only get tougher thanks to the inevitable closure of smaller schools and a general preference for adjuncts over tenure-track professors. Ph.D. programs do not limit the number of students they accept based on the anticipated number of professorial job openings. There are many more Ph.D.s than professorships!Even if you do get your dream job in academia, you’ll probably hate it and/or lose it

I don’t think I know of a single professor, tenured or otherwise, who loves their job. They need to take on a huge teaching load thanks to the dearth of adjuncts and/or assume administrative positions that do not incur an increased salary.The financial implications and opportunity cost of leaving your job for three to ten years

Some studies have concluded that getting a Ph.D. will require up to fifty years to outweigh the opportunity cost of staying in the workforce and advancing your career. But in some circumstances it can be as few as five years. This is because there is a lot of variance in the compensation for graduate students. Be prepared for three to ten years of significantly reduced income.The Snake Fight

Beware.Common reasons you will fail

There are myriad reasons why you might fail to complete your Ph.D. that are almost all completely out of your control.Survivor bias is real. Trust me, I’m a survivor.

Only two out of the ~dozen students in my research lab ever completed their degree. Keep that in mind when you take advice from the survivors.Someone “scoops” your research

This is typically more of an issue in the more theoretical specializations, but it does happen. If someone solves your problem before you, you’ve got to start over. I’ve written an essay about this.Your advisor switches schools

Sometimes this can be a good thing; for example, a friend of mine’s advisor transferred from an average school to MIT right before my friend graduated, and he was able to transfer over all of his credits, defend at MIT, and get MIT on his diploma. But I also know a bunch of people who were bitten by this, where the new school would not accept their credits and/or there was no funding at the new school for tuition remission and a stipend, so they basically had to drop out.Your advisor goes on sabbatical

It’s hard to be advised if your advisor is off galavanting for a year or two. Good advisors plan for this, but I know of several cases where students had to drop out because their advisor didn’t plan ahead.You don’t get along with your advisor, or they go AWOL, or their tenure application is denied, (or they die)

Ever look at a 101-level STEM textbook? There are usually at least two authors: The one who knows what they’re talking about, and the one who speaks English as a native language. I had two advisors for basically the same reason. My first advisor had lots of research grants and contracts which afforded me tuition remission and a good stipend. But that work was mostly applied science; nothing was deep enough to turn into a thesis topic. So I took on a co-advisor who had just been hired as a new tenure-track professor and was full of cool ideas. A few months later he unfortunately, suddenly, died. Then I took on a third co-advisor (who was happy to take me on because he didn’t have to worry about paying me from his own grants). This amounted to more work for me, since I had to do the work to “pay the bills” with my original advisor as well as my actual research with my new co-advisor. But it also gave me a bunch of freedom to just work on what I wanted. With that said, I had two labmates who were working under my late co-advisor who were unable to find a place for themselves after his death, and never completed their dissertations. A lot of it is luck. If a professor’s tenure application is denied, they are usually given a year to wrap up their business and leave the school. Most departments have contingency plans to pair orphaned graduate students with new advisors, but this can be a devastating blow to most students, for all intents and purposes similar to their passing away.You don’t have enough time to focus on your research

In my case, I was effectively working a full time job doing applied research for my first advisor in addition to being a “regular” graduate student with my co-advisor. This entailed 60+ hour work weeks for basically my entire Ph.D. It’s super hard to focus on research if you have a full time job; I only know of one or two people who successfully completed a part-time Ph.D. while working a full time job at the same time.You still want to get a Ph.D.?

Things you need to do before applying

Do you already have a master’s degree?

Some schools in the US do not require you to take any classes, while most others require you to effectively earn a Master’s in the process of getting your Ph.D. If you do not have a Master’s yet, try and choose a school that effectively forces you to earn a Master’s in the process of getting a Ph.D., as that will be a nice consolation prize in the event that you do not complete your dissertation. If you do have a Master’s, check on your prospective school’s degree requirements and whether they will accept your existing credits. If a school requires you to take a bunch of classes and you don’t want to earn a second Master’s, make sure they will waive that requirement for you. This affected me when I was deciding on which program to join, since I already had a Master’s and many schools wouldn’t budge on forcing me to re-do all of my Master’s classes.Decide in what you want to specialize

More on this below, but it’s best if you know what you want to research before you apply to a program. You don’t choose a school for a Ph.D. the same way you choose a school for an undergrad or even a Master’s degree. Choose the school based upon how your desired research aligns with what the professors there are doing, not based upon the name or prestige of the school.Read the entire Ph.D. Comics archive

Seriously, it’s really good, and completely accurate.How to get into a good program

Find potential advisors first

Compile a list of everyone who is actively doing research in an area related to your desired specialization. Send them an E-mail stating your desire to pursue a Ph.D. Ask them if they are taking on new students, and, if so, what their time frame is. The easiest way to get accepted to a Ph.D. program is to have a professor advocating on your behalf. If a professor wants to work with you, they can guide and even fast-track you through the admissions process.You should not have to pay your way through a Computer Science Ph.D.

Don’t expect to be rich, but every decent computer science Ph.D. program should offer tuition remission and a slightly-above-the-poverty-line stipend, either by acting as a teaching assistant (TA) or as a research assistant (RA). Do not accept any less. If the school wants you to pay for your Ph.D., something is wrong. Being an RA is preferable to a TA.Having a source of external funding lined up will get you into almost any school

The biggest limiting factor in taking on new students both at the departmental and professorial levels is funding. A professor will not advise a new student unless they have enough funding (either through grants/contracts that fund RA-ship, or through departmental TA-ships). If there are no TA openings and/or the professor doesn’t have enough grant funding to pay for your stipend and tuition remission, then they won’t take you on as a student. In such situations, you can either pay for your own tuition and forego a stipend (never, ever, do this!), or you can come to the table with your own external source of funding! This can be through a grant program (e.g., the NSF GRFP). If a professor doesn’t have to worry about how to “feed” you, they’ll be thrilled to work with you, and it will give you a lot more freedom in directing your own research.How to minimize your chances of failing

Talk to your potential advisor’s current and past students

Do this preferably before even applying. How many of the professor’s students actually graduate? Where do they end up after graduation? How many papers does each student publish per year? How is travel to conferences funded? What is the professor’s advising style like? This will vary drastically from professor to professor.

I’d be lucky to talk to one of my co-advisors once a month.

What is the professor’s advising style like? This will vary drastically from professor to professor.

I’d be lucky to talk to one of my co-advisors once a month.

My other co-advisor would actually sit down with me 1-on-1 and we’d read aloud a new paper together,

sentence-by-sentence, ensuring that we each understood what was written before moving on. Some people might hate that,

though. Different styles work for different kinds of students. Some professors demand that you work on a specific

problem they have defined, whereas others expect you to carve out your research topic yourself. Determine what type of

advisor you think you need, and interview existing students to see if the professor meets your needs.

My other co-advisor would actually sit down with me 1-on-1 and we’d read aloud a new paper together,

sentence-by-sentence, ensuring that we each understood what was written before moving on. Some people might hate that,

though. Different styles work for different kinds of students. Some professors demand that you work on a specific

problem they have defined, whereas others expect you to carve out your research topic yourself. Determine what type of

advisor you think you need, and interview existing students to see if the professor meets your needs.

Interview your potential advisor in advance

What is a typical week in the life of an advisee like? How many regular meetings are there? How often do students typically meet with their advisor 1-on-1? Will the professor expect you to take any specific classes, regardless of the school’s degree requirements? Professors will often require you to take certain classes they think are really good. Is the professor planning to go on sabbatical any time soon? Do they have tenure? (Typically, professors will earn and usually take a sabbatical shortly after earning tenure. If a professor applies for tenure and is denied, they usually only get a year before they are fired. Some schools give professors two chances at getting tenure.) What is the professor’s teaching load like? Would they expect you to teach and/or TA? Or could you be an RA full time? What is their research grant pipeline like? When do their current grants end?Choose a topic that is unlikely to be “scooped”

I already linked to this above, but please read this essay I wrote. Try and choose a dissertation topic that can’t be duplicated by someone else first. This usually means choosing a topic that—even if it is inherently theoretical—could worst-case be “proven” empirically in the event that you can’t prove it formally.Remember that your dissertation is unlikely to ever be read by anyone other than your committee members

It is, in a sense, a rite of passage. If you don’t intend to go into academia, there is no shame in doing the minimum amount possible that can get you graduated. With that said, my dissertation is super awesome and you should totally read it right now. Plz, become the sixth person to have ever read it.

What to expect after you have a Ph.D.

Breaking into Google Headquarters

In which I tempt the criminal justice system while flaunting the California statute of limitations.

Fifteen years ago, a handful of my grad school labmates and I found ourselves at the brand new Googleplex. Dear reader, I think it’s finally safe for me to tell the story of that one time I trespassed into Google’s headquarters and took a bunch of pictures.

It was 8pm on a Wednesday. I don’t think Google had finished moving to the new campus yet, so it was relatively quiet. We wanted to take a peek inside, but the lobby was locked and there was no one at the front desk. So we did what any reasonable group of bored grad students would have done: We loitered on the side of a footpath, waited for the inevitable, unsuspecting Google employee returning from dinner to burn the midnight oil at work, and tailgated the RFID-card-clutching-rube through a locked external door. The door opened into a stairwell, the interior door of which led to the main lobby.

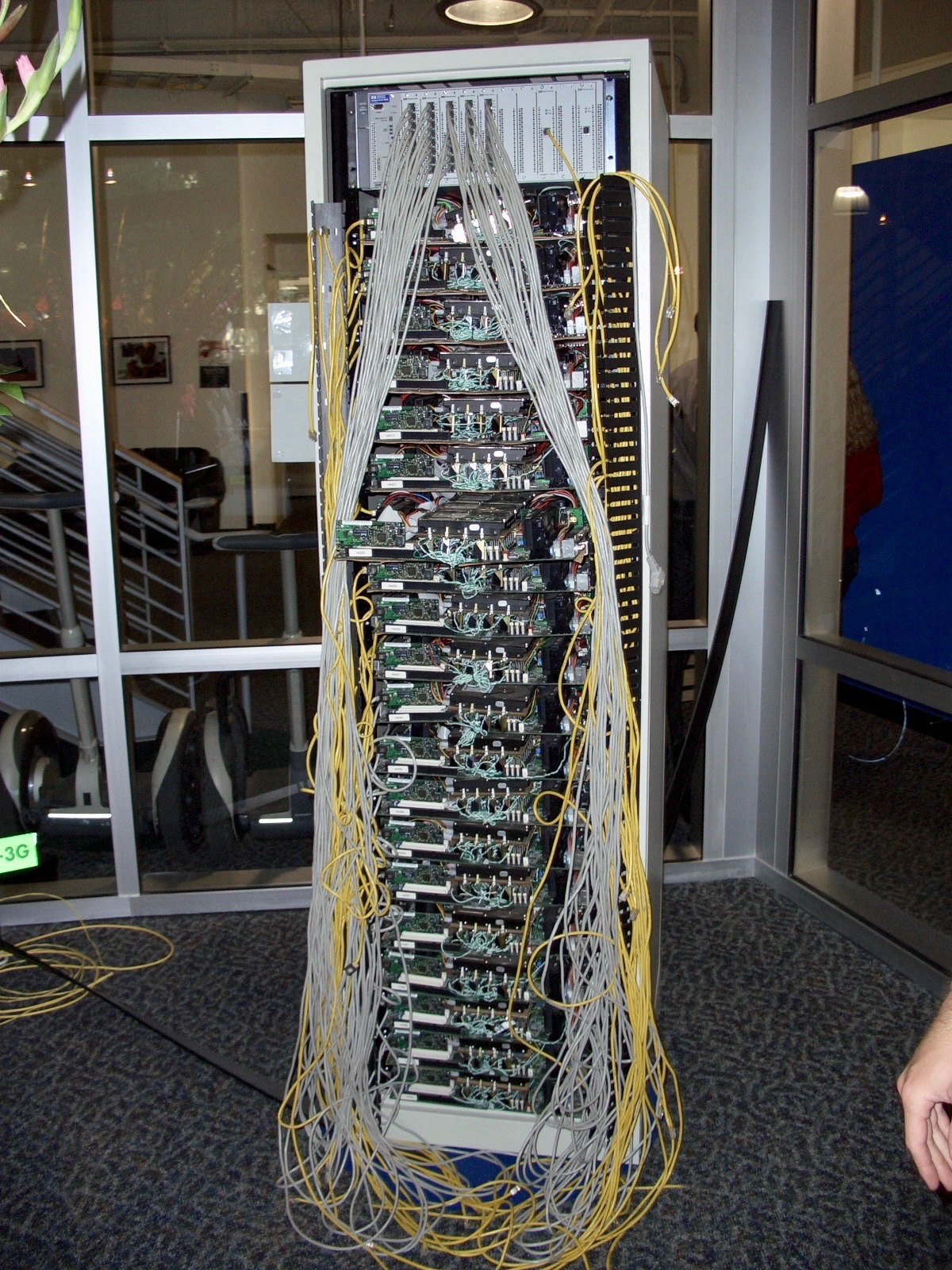

The lobby was odd, decorated with an unlabeled server rack, the cable management of which would make any sysadmin’s eyes bleed. We speculated that this might have been the rig that served the first version of Google, but there didn’t seem to be anything to confirm it. It was just a hacked together server rack filling a corner.

In case you doubted my claim that our story takes place during the heady days of 2004, the lobby was replete with a Segway parking area.

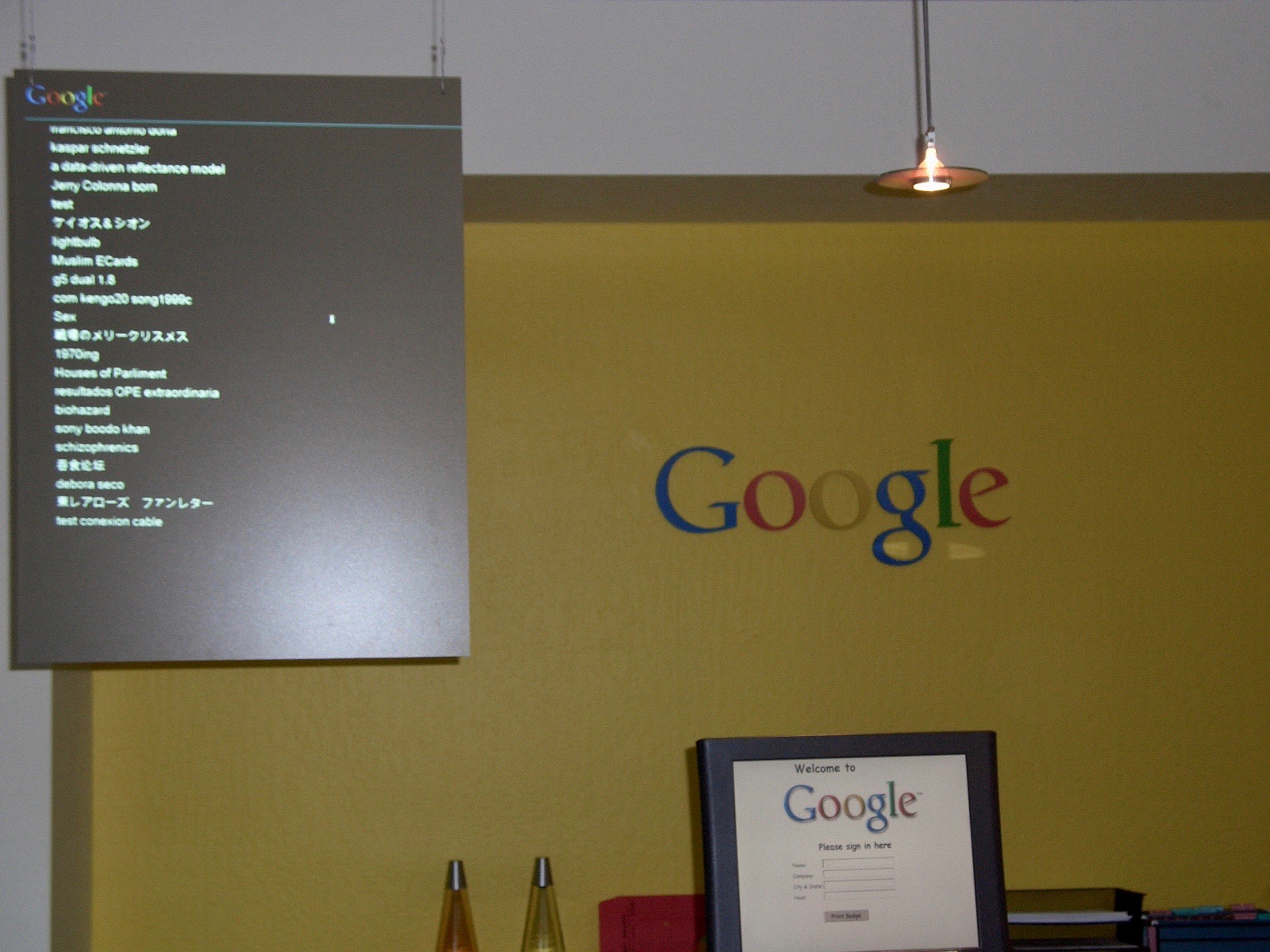

There was a large screen with a live stream of ostensibly unfiltered Google search queries. Despite being unstaffed, the computer at the reception desk was unlocked. So … there was no one to stop us from printing ourselves official Google visitor credentials.

Unfortunately, “God’s-gift-to-Google” didn’t entirely fit.

Did I mention alcohol was involved? The identities of my accomplices have been hidden to protect the guilty. With our newly minted credentials, we made our way upstairs.

We quickly stumbled upon Brin and Page’s shared office. Looks like they were Homestar Runner fans! Also, lol, jewel cases.

Another shared office filled with some big names, and space for one more.

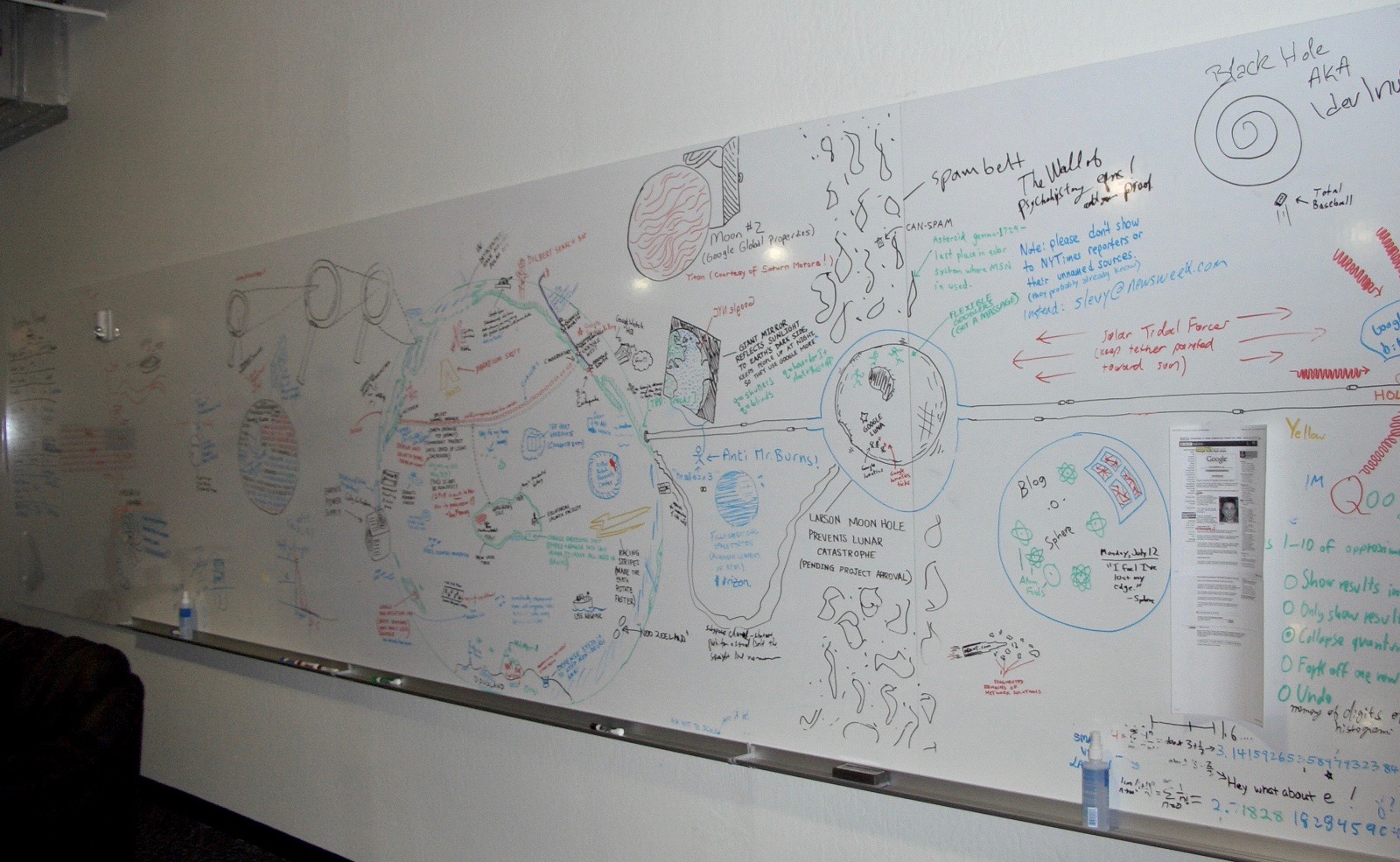

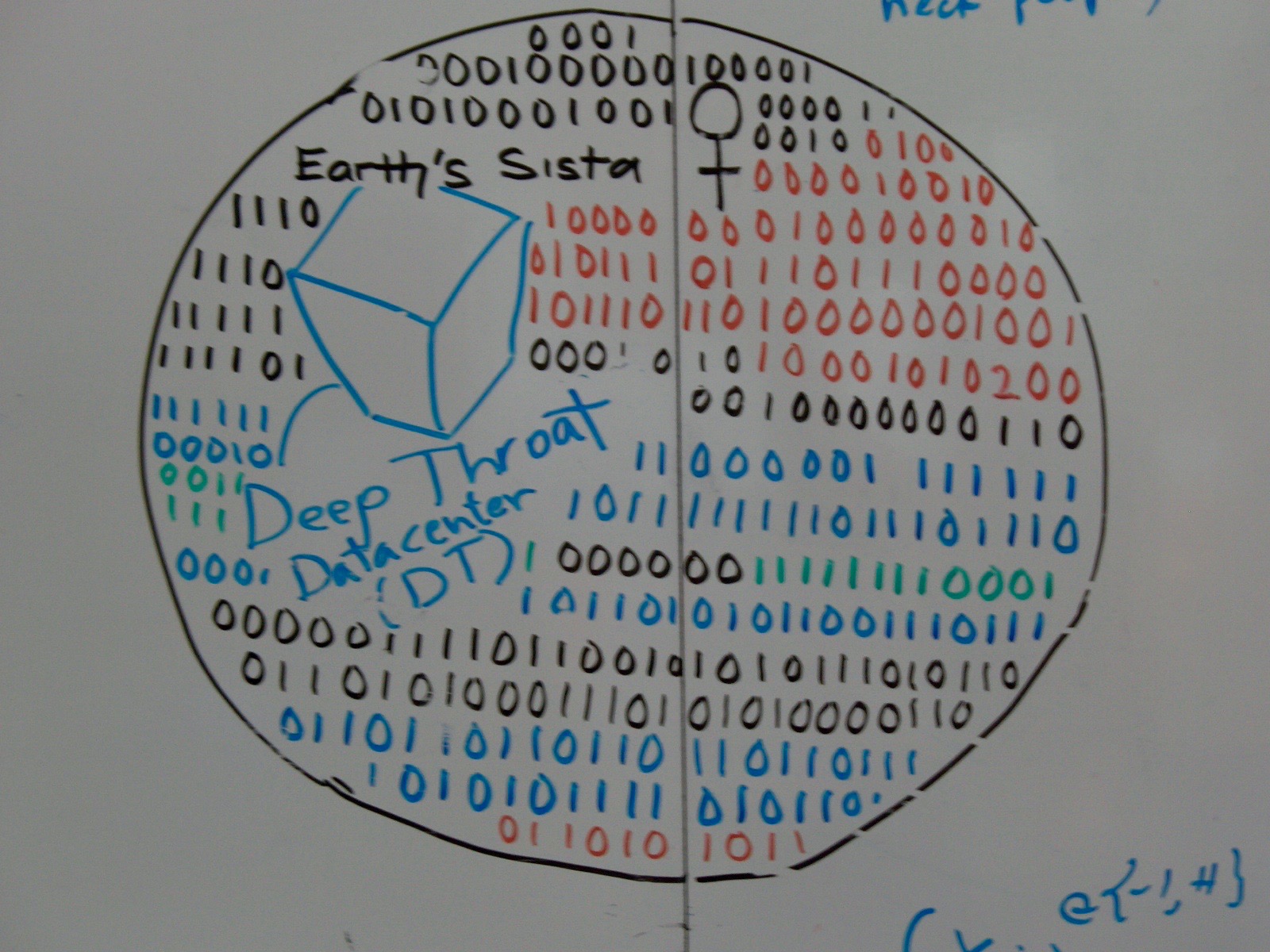

That’s some proprietary information right there! I guess Google hasn’t gotten to that giant space mirror yet. Finally, I leave you with the following whiteboard pic.

PoC‖GTFO

PoC‖GTFO Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn GitHub

GitHub XTerm

XTerm

Esperanto

Esperanto

עברית

עברית

Medžuslovjansky

Medžuslovjansky

Русский

Русский