Recent Content:

I recently attended the AI Engineer Code Summit in New York, an invite-only gathering of AI leaders and engineers. One theme emerged repeatedly in conversations with attendees building with AI: the belief that we’re approaching a future where developers will never need to look at code again. When I pressed these proponents, several made a similar argument:

Forty years ago, when high-level programming languages like C became increasingly popular, some of the old guard resisted because C gave you less control than assembly. The same thing is happening now with LLMs.

On its face, this analogy seems reasonable. Both represent increasing abstraction. Both initially met resistance. Both eventually transformed how we write software. But this analogy really thrashes my cache because it misses a fundamental distinction that matters more than abstraction level: determinism.

The difference between compilers and LLMs isn’t just about control or abstraction. It’s about semantic guarantees. And as I’ll argue, that difference has profound implications for the security and correctness of software.

As I wrote back in 2017 in “Automation of Automation,” there are fundamental limits on what we can automate. But those limits don’t eliminate determinism in the tools we’ve built; they simply mean we can’t automatically prove every program correct. Compilers don’t try to prove your program correct; they just faithfully translate it.

Speedrunning the New York Subway

in which I am nerd-sniped into finding the shortest route that visits every NYC subway station

It all began, as many great adventures do, at Empire Hacking. There, I encountered the inimitable @ImmigrantJackson, a YouTuber with a penchant for public transit and a dream: to break the world record for visiting every subway stop in New York City in the least time possible. (And, of course, to film the journey, what for those delicious likes, comments, and subscriptions.)

The only problem was: Immigrant Jackson didn’t know the fastest route. Surrounded by a room full of Trail of Bits computer scientists, he figured he’d ask our advice. The rules were simple. He didn’t need to exit the subway car; simply passing through a stop, even on an express train, counted as a “visit.” Stops could be visited multiple times, although this would of course be suboptimal. And there was no need to visit Staten Island … because we’re civilized. We live in a society. So, where should he start, and what would be the best route?

The coterie of curious computer coders coalescing around the inquisitor quickly classified this question as a case of the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP). TSP is a classical problem in computer science in which one must find the shortest route for a traveling salesman to visit each city on a map. TSP is known to be computationally intractable to solve optimally for networks even as small as the New York subway system. Therefore, everyone dismissed the problem as “impossible.”

Except for me.

You see, my now-ancient PhD dissertation was on combinatorial optimization and approximation algorithms: tools for solving problems like TSP efficiently with a result that is not necessarily optimal, but at least close to optimal. I knew that there were algorithms capable of solving TSP very quickly, producing a route guaranteed to be at most 50% longer than the optimal solution. In fact, one of the results of my dissertation was the surprising revelation that even if you choose a feasible route at random, it will, on average, be only thrice the length of the optimal solution.

This, dear reader, was how I was nerd-sniped into optimizing (speedrunning?) the NYC subway.

The first challenge was that, even when you discard Staten Italy, the subway system still has a lot of stations. There are close to 500. This exercise was fun and all, but I wasn’t about to spend hours encoding hundreds of stations, lines, transfer points, headways, and average trip times into a program.

There is an open standard for specifying public transit data: the General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS). Fortunately, the MTA has a public API implementing GTFS. It’s just a collection of CSV files that are quite straightforward to parse. The dataset is sufficient to construct a graph with a node for each subway station and an edge if there is a subway line that connects the two stations. Actually, the data represents subway platforms rather than stations, which is necessary to calculate things like transfer times between train lines.

The New York Subway network is a directed graph: some neighboring stations are accessible to each other only in one direction. For example, the Aqueduct Racetrack station only has a platform for northbound trains, not southbound trains. The best algorithms for approximating a solution to TSP on directed graphs are not great, only guaranteeing a solution of three or four times the length of the optimal solution. Therefore, I decided to relax the problem to an undirected graph (i.e., I assume that every station has trains to its neighbors bidirectionally). This turned out not to be an issue and permitted the use of the Christofides algorithm, which guarantees a solution at most 50% longer than optimal.

The next and final relaxation is to partially ignore actual timetables and headways. When a transfer between lines is necessary, I assume that the transfer will require the “minimum transfer time” reported by GTFS (i.e., the amount of time required to walk from one platform to another) plus one-half the average headway for that line throughout the day. Therefore, the resulting route has the potential to strand the poor YouTuber on the last train at the end of a line. Validating the resulting route’s real-world feasibility is left as an exercise to the reader.

The Christofides algorithm was able to approximate a solution to the TSP for my relaxed subway network graph in a matter of milliseconds. This is compared to the unfathomable amount of computation required to brute-force calculate the optimal solution, an amount so large that it afforded me the horrifying opportunity to learn that there is a whole community of “googologists” who compete with each other to name large numbers. We’re talking googolchime levels of computation. Guppybell levels, even!

The resulting tour visits all 474 stations, 155 of which are visited more than once. The tour requires 34 transfers. The expected time for completing this tour is 20 hours, 42 minutes. That’s about 45 minutes faster than the record, which was about 21 and a half hours.

This is neat and all, but we spent an unnecessary amount of energy encoding the New York subway system as a graph. What else might we do with it? One straightforward computation is to calculate each station’s eigenvector centrality. Imagine you’re given the Sisyphean task of riding the subway for all eternity. Every time you arrive at a station, you flip a coin. If it’s heads, you stay on the current train. If it’s tails, you get off and transfer to another line or direction. If you were to pause your infinite tour at any arbitrary point in time, what’s the probability that you are at a particular station? The higher the probability, the more “centrally connected” the station. That’s exactly what eigenvector centrality calculates.

Eigenvector centrality is actually what Google originally used in its PageRank algorithm to rank the relative importance (centrality) of web pages. Each page is like a subway station, and hyperlinks on the page are like the subway lines connecting them. Eigenvector centrality is relatively easy to calculate, either directly (it’s related to the eigenspectrum of the graph’s adjacency matrix, thanks to spooky spectral graph theory magic) or using a technique called power iteration (which relies on a convergence that happens when you multiply the adjacency matrix by a vector a bunch of times). Either way, you can calculate it with a single function call in NetworkX.

What do you think will be the most probable stop on your infinite subway tour? Or, another way to ask the same question: Which stop will you visit most often on your tour? Unsurprisingly, it will be Times Square, with a probability of a little over 30%. The next most probable station is 42nd St. Port Authority Bus Terminal, coming in at about 8%. Then 50th St., 59th St. Columbus Circle, Grand Central 42nd St., and 34th St. Penn Station are all between 4% and 5%.

So, what have we learned? First of all, don’t attend Empire Hacking without the expectation of being intellectually stimulated. Secondly, don’t immediately discount a problem just because it is NP-hard or computationally intractable to solve; you might be able to approximate a solution of sufficient optimality. Thirdly, Times Square may not be the “center of the universe,” but it is definitely the center of the New York subway system. Finally, remember to like, comment, and subscribe!

Click to see the complete tour route!

1 (0.0hrs): Far Rockaway-Mott Av2 (0.0hrs): Beach 25 St

3 (0.1hrs): Beach 36 St

4 (0.1hrs): Beach 44 St

5 (0.1hrs): Beach 60 St

6 (0.1hrs): Beach 67 St

7 (0.2hrs): Broad Channel

8 (0.3hrs): Beach 90 St

9 (0.3hrs): Beach 98 St

10 (0.3hrs): Beach 105 St

11 (0.4hrs): Rockaway Park-Beach 116 St

12 (0.4hrs): Beach 105 St (visit 2)

13 (0.4hrs): Beach 98 St (visit 2)

14 (0.4hrs): Beach 90 St (visit 2)

15 (0.5hrs): Broad Channel (visit 2)

16 (0.6hrs): Howard Beach-JFK Airport

17 (0.7hrs): Aqueduct-N Conduit Av

18 (0.7hrs): Aqueduct Racetrack

19 (0.7hrs): Rockaway Blvd

20 (0.8hrs): 104 St

21 (0.8hrs): 111 St

22 (0.9hrs): Ozone Park-Lefferts Blvd

23 (0.9hrs): 111 St (visit 2)

24 (0.9hrs): 104 St (visit 2)

25 (0.9hrs): Rockaway Blvd (visit 2)

26 (0.9hrs): 88 St

27 (1.0hrs): 80 St

28 (1.0hrs): Grant Av

29 (1.0hrs): Euclid Av

30 (1.0hrs): Shepherd Av

31 (1.1hrs): Van Siclen Av

32 (1.1hrs): Liberty Av

33 (1.1hrs): Broadway Junction

transfer lines

34 (1.2hrs): Broadway Junction

35 (1.2hrs): Alabama Av

36 (1.3hrs): Van Siclen Av

37 (1.3hrs): Cleveland St

38 (1.3hrs): Norwood Av

39 (1.3hrs): Crescent St

40 (1.4hrs): Cypress Hills

41 (1.4hrs): 75 St-Elderts Ln

42 (1.4hrs): 85 St-Forest Pkwy

43 (1.4hrs): Woodhaven Blvd

44 (1.5hrs): 104 St

45 (1.5hrs): 111 St

46 (1.5hrs): 121 St

47 (1.6hrs): Sutphin Blvd-Archer Av-JFK Airport

48 (1.7hrs): Jamaica Center-Parsons/Archer

49 (1.7hrs): Sutphin Blvd-Archer Av-JFK Airport (visit 2)

50 (1.7hrs): Jamaica-Van Wyck

51 (1.7hrs): Briarwood

52 (1.8hrs): Sutphin Blvd

53 (1.8hrs): Parsons Blvd

54 (1.9hrs): 169 St

55 (2.0hrs): Jamaica-179 St

56 (2.0hrs): 169 St (visit 2)

57 (2.0hrs): Parsons Blvd (visit 2)

58 (2.1hrs): Sutphin Blvd (visit 2)

59 (2.1hrs): Briarwood (visit 2)

60 (2.1hrs): Kew Gardens-Union Tpke

61 (2.2hrs): 75 Av

62 (2.2hrs): Forest Hills-71 Av

63 (2.2hrs): 67 Av

64 (2.2hrs): 63 Dr-Rego Park

65 (2.3hrs): Woodhaven Blvd

66 (2.3hrs): Grand Av-Newtown

67 (2.3hrs): Elmhurst Av

68 (2.4hrs): Jackson Hts-Roosevelt Av

69 (2.4hrs): 65 St

70 (2.4hrs): Northern Blvd

71 (2.4hrs): 46 St

72 (2.5hrs): Steinway St

73 (2.5hrs): 36 St

74 (2.5hrs): Queens Plaza

75 (2.6hrs): Court Sq-23 St

76 (2.6hrs): Lexington Av/53 St

77 (2.6hrs): 5 Av/53 St

78 (2.7hrs): 7 Av

79 (2.7hrs): 50 St

80 (2.7hrs): 42 St-Port Authority Bus Terminal

81 (2.8hrs): 34 St-Penn Station

82 (2.8hrs): 23 St

83 (2.8hrs): 14 St

84 (2.9hrs): W 4 St-Wash Sq

85 (2.9hrs): Spring St

86 (2.9hrs): Canal St

87 (2.9hrs): World Trade Center

88 (3.0hrs): Canal St (visit 2)

89 (3.0hrs): Chambers St

90 (3.0hrs): Fulton St

transfer lines

91 (3.1hrs): Fulton St

92 (3.1hrs): Wall St

93 (3.1hrs): Bowling Green

94 (3.2hrs): Wall St (visit 2)

95 (3.2hrs): Fulton St (visit 2)

96 (3.2hrs): Brooklyn Bridge-City Hall

97 (3.2hrs): Canal St

98 (3.3hrs): Brooklyn Bridge-City Hall (visit 2)

transfer lines

99 (3.3hrs): Chambers St

100 (3.4hrs): Fulton St

101 (3.4hrs): Broad St

102 (3.4hrs): Fulton St (visit 2)

103 (3.4hrs): Chambers St (visit 2)

104 (3.5hrs): Canal St

105 (3.5hrs): Bowery

106 (3.5hrs): Delancey St-Essex St

107 (3.6hrs): Bowery (visit 2)

108 (3.6hrs): Canal St (visit 2)

transfer lines

109 (3.6hrs): Canal St (visit 2)

110 (3.7hrs): Spring St

111 (3.7hrs): Bleecker St

112 (3.7hrs): Astor Pl

113 (3.7hrs): 14 St-Union Sq

114 (3.8hrs): 23 St

115 (3.8hrs): 28 St

116 (3.8hrs): 33 St

117 (3.8hrs): Grand Central-42 St

118 (3.9hrs): 51 St

119 (3.9hrs): 59 St

120 (3.9hrs): 68 St-Hunter College

121 (3.9hrs): 77 St

122 (4.0hrs): 86 St

123 (4.0hrs): 96 St

124 (4.0hrs): 103 St

125 (4.0hrs): 110 St

126 (4.1hrs): 116 St

127 (4.1hrs): 125 St

128 (4.1hrs): 3 Av-138 St

129 (4.3hrs): Hunts Point Av

130 (4.4hrs): Parkchester

131 (4.4hrs): Castle Hill Av

132 (4.4hrs): Zerega Av

133 (4.4hrs): Westchester Sq-E Tremont Av

134 (4.5hrs): Middletown Rd

135 (4.5hrs): Buhre Av

136 (4.5hrs): Pelham Bay Park

137 (4.6hrs): Buhre Av (visit 2)

138 (4.6hrs): Middletown Rd (visit 2)

139 (4.6hrs): Westchester Sq-E Tremont Av (visit 2)

140 (4.6hrs): Zerega Av (visit 2)

141 (4.7hrs): Castle Hill Av (visit 2)

142 (4.7hrs): Parkchester (visit 2)

143 (4.7hrs): St Lawrence Av

144 (4.7hrs): Morrison Av-Soundview

145 (4.8hrs): Elder Av

146 (4.8hrs): Whitlock Av

147 (4.8hrs): Hunts Point Av (visit 2)

148 (4.8hrs): Longwood Av

149 (4.9hrs): E 149 St

150 (4.9hrs): E 143 St-St Mary’s St

151 (4.9hrs): Cypress Av

152 (4.9hrs): Brook Av

153 (5.0hrs): 3 Av-138 St (visit 2)

154 (5.0hrs): 125 St (visit 2)

155 (5.1hrs): 138 St-Grand Concourse

156 (5.1hrs): 149 St-Grand Concourse

transfer lines

157 (5.2hrs): 149 St-Grand Concourse

158 (5.2hrs): 3 Av-149 St

159 (5.4hrs): E 180 St

160 (5.4hrs): Morris Park

161 (5.5hrs): Pelham Pkwy

162 (5.5hrs): Gun Hill Rd

163 (5.5hrs): Baychester Av

164 (5.6hrs): Eastchester-Dyre Av

165 (5.6hrs): Baychester Av (visit 2)

166 (5.7hrs): Gun Hill Rd (visit 2)

167 (5.7hrs): Pelham Pkwy (visit 2)

168 (5.7hrs): Morris Park (visit 2)

169 (5.8hrs): E 180 St (visit 2)

170 (5.8hrs): Bronx Park East

171 (5.9hrs): Pelham Pkwy

172 (5.9hrs): Allerton Av

173 (5.9hrs): Burke Av

174 (5.9hrs): Gun Hill Rd

175 (6.0hrs): 219 St

176 (6.0hrs): 225 St

177 (6.0hrs): 233 St

178 (6.0hrs): Nereid Av

179 (6.1hrs): Wakefield-241 St

180 (6.1hrs): Nereid Av (visit 2)

181 (6.2hrs): 233 St (visit 2)

182 (6.2hrs): 225 St (visit 2)

183 (6.2hrs): 219 St (visit 2)

184 (6.2hrs): Gun Hill Rd (visit 2)

185 (6.4hrs): E 180 St (visit 3)

186 (6.4hrs): West Farms Sq-E Tremont Av

187 (6.4hrs): 174 St

188 (6.5hrs): Freeman St

189 (6.5hrs): Simpson St

190 (6.5hrs): Intervale Av

191 (6.5hrs): Prospect Av

192 (6.6hrs): Jackson Av

193 (6.6hrs): 3 Av-149 St (visit 2)

194 (6.6hrs): 149 St-Grand Concourse (visit 2)

195 (6.7hrs): 135 St

196 (6.7hrs): 145 St

197 (6.8hrs): Harlem-148 St

198 (6.8hrs): 145 St (visit 2)

199 (6.8hrs): 135 St (visit 2)

200 (6.9hrs): 125 St

201 (6.9hrs): 116 St

202 (6.9hrs): Central Park North (110 St)

203 (7.0hrs): 96 St

204 (7.0hrs): 72 St

205 (7.1hrs): 66 St-Lincoln Center

206 (7.1hrs): 59 St-Columbus Circle

transfer lines

207 (7.1hrs): 59 St-Columbus Circle

208 (7.2hrs): 7 Av (visit 2)

209 (7.2hrs): 47-50 Sts-Rockefeller Ctr

210 (7.2hrs): 57 St

211 (7.2hrs): 47-50 Sts-Rockefeller Ctr (visit 2)

212 (7.3hrs): 42 St-Bryant Pk

213 (7.3hrs): 34 St-Herald Sq

214 (7.3hrs): 23 St

215 (7.3hrs): 14 St

216 (7.4hrs): W 4 St-Wash Sq

217 (7.4hrs): Broadway-Lafayette St

218 (7.4hrs): Grand St

219 (7.5hrs): Broadway-Lafayette St (visit 2)

220 (7.5hrs): 2 Av

221 (7.5hrs): Delancey St-Essex St

222 (7.6hrs): East Broadway

223 (7.6hrs): York St

224 (7.6hrs): Jay St-MetroTech

transfer lines

225 (7.7hrs): Jay St-MetroTech

226 (7.7hrs): DeKalb Av

227 (7.7hrs): Atlantic Av-Barclays Ctr

228 (7.8hrs): 7 Av

229 (7.8hrs): Prospect Park

230 (7.9hrs): Parkside Av

231 (7.9hrs): Church Av

232 (7.9hrs): Beverley Rd

233 (7.9hrs): Cortelyou Rd

234 (8.0hrs): Newkirk Plaza

235 (8.0hrs): Avenue H

236 (8.0hrs): Avenue J

237 (8.0hrs): Avenue M

238 (8.1hrs): Kings Hwy

239 (8.1hrs): Avenue U

240 (8.1hrs): Neck Rd

241 (8.2hrs): Sheepshead Bay

242 (8.2hrs): Brighton Beach

243 (8.2hrs): Ocean Pkwy

244 (8.3hrs): W 8 St-NY Aquarium

245 (8.3hrs): Coney Island-Stillwell Av

246 (8.3hrs): W 8 St-NY Aquarium (visit 2)

247 (8.4hrs): Neptune Av

248 (8.4hrs): Avenue X

249 (8.4hrs): Avenue U

250 (8.4hrs): Kings Hwy

251 (8.5hrs): Avenue P

252 (8.5hrs): Avenue N

253 (8.5hrs): Bay Pkwy

254 (8.5hrs): Avenue I

255 (8.6hrs): 18 Av

256 (8.6hrs): Ditmas Av

257 (8.6hrs): Church Av

258 (8.6hrs): Fort Hamilton Pkwy

259 (8.7hrs): 15 St-Prospect Park

260 (8.7hrs): 7 Av

261 (8.7hrs): 4 Av-9 St

262 (8.8hrs): Smith-9 Sts

263 (8.8hrs): Carroll St

264 (8.8hrs): Bergen St

265 (8.9hrs): Hoyt-Schermerhorn Sts

266 (8.9hrs): Lafayette Av

267 (8.9hrs): Clinton-Washington Avs

268 (8.9hrs): Franklin Av

transfer lines

269 (9.0hrs): Franklin Av

transfer lines

270 (9.0hrs): Franklin Av (visit 2)

271 (9.1hrs): Nostrand Av

272 (9.1hrs): Kingston-Throop Avs

273 (9.1hrs): Utica Av

274 (9.2hrs): Ralph Av

275 (9.2hrs): Rockaway Av

276 (9.2hrs): Broadway Junction (visit 2)

transfer lines

277 (9.3hrs): Broadway Junction

278 (9.3hrs): Atlantic Av

279 (9.3hrs): Sutter Av

280 (9.3hrs): Livonia Av

281 (9.4hrs): New Lots Av

282 (9.4hrs): East 105 St

283 (9.4hrs): Canarsie-Rockaway Pkwy

284 (9.4hrs): East 105 St (visit 2)

285 (9.5hrs): New Lots Av (visit 2)

286 (9.5hrs): Livonia Av (visit 2)

transfer lines

287 (9.6hrs): Junius St

288 (9.6hrs): Pennsylvania Av

289 (9.6hrs): Van Siclen Av

290 (9.7hrs): New Lots Av

291 (9.7hrs): Van Siclen Av (visit 2)

292 (9.7hrs): Pennsylvania Av (visit 2)

293 (9.7hrs): Junius St (visit 2)

294 (9.7hrs): Rockaway Av

295 (9.8hrs): Saratoga Av

296 (9.8hrs): Sutter Av-Rutland Rd

297 (9.8hrs): Crown Hts-Utica Av

298 (9.9hrs): Kingston Av

299 (9.9hrs): Nostrand Av

300 (9.9hrs): Franklin Av-Medgar Evers College

301 (10.0hrs): President St-Medgar Evers College

302 (10.0hrs): Sterling St

303 (10.0hrs): Winthrop St

304 (10.1hrs): Church Av

305 (10.1hrs): Beverly Rd

306 (10.2hrs): Newkirk Av-Little Haiti

307 (10.2hrs): Flatbush Av-Brooklyn College

308 (10.2hrs): Newkirk Av-Little Haiti (visit 2)

309 (10.2hrs): Beverly Rd (visit 2)

310 (10.3hrs): Church Av (visit 2)

311 (10.3hrs): Winthrop St (visit 2)

312 (10.3hrs): Sterling St (visit 2)

313 (10.3hrs): President St-Medgar Evers College (visit 2)

314 (10.4hrs): Franklin Av-Medgar Evers College (visit 2)

315 (10.4hrs): Eastern Pkwy-Brooklyn Museum

316 (10.5hrs): Grand Army Plaza

317 (10.5hrs): Bergen St

318 (10.5hrs): Atlantic Av-Barclays Ctr

transfer lines

319 (10.6hrs): Atlantic Av-Barclays Ctr

320 (10.7hrs): 36 St

321 (10.7hrs): 9 Av

322 (10.8hrs): Fort Hamilton Pkwy

323 (10.8hrs): 50 St

324 (10.8hrs): 55 St

325 (10.8hrs): 62 St

transfer lines

326 (10.9hrs): New Utrecht Av

327 (10.9hrs): 18 Av

328 (10.9hrs): 20 Av

329 (11.0hrs): Bay Pkwy

330 (11.0hrs): Kings Hwy

331 (11.0hrs): Avenue U

332 (11.0hrs): 86 St

333 (11.1hrs): Coney Island-Stillwell Av (visit 2)

334 (11.2hrs): Bay 50 St

335 (11.3hrs): 25 Av

336 (11.3hrs): Bay Pkwy

337 (11.3hrs): 20 Av

338 (11.3hrs): 18 Av

339 (11.3hrs): 79 St

340 (11.4hrs): 71 St

341 (11.4hrs): 62 St (visit 2)

transfer lines

342 (11.5hrs): New Utrecht Av (visit 2)

343 (11.5hrs): Fort Hamilton Pkwy

344 (11.5hrs): 8 Av

345 (11.6hrs): 59 St

346 (11.6hrs): Bay Ridge Av

347 (11.6hrs): 77 St

348 (11.7hrs): 86 St

349 (11.7hrs): Bay Ridge-95 St

350 (11.7hrs): 86 St (visit 2)

351 (11.8hrs): 77 St (visit 2)

352 (11.8hrs): Bay Ridge Av (visit 2)

353 (11.8hrs): 59 St (visit 2)

354 (11.9hrs): 53 St

355 (11.9hrs): 45 St

356 (11.9hrs): 36 St (visit 2)

357 (12.0hrs): 25 St

358 (12.0hrs): Prospect Av

359 (12.0hrs): 4 Av-9 St

360 (12.0hrs): Union St

361 (12.1hrs): Atlantic Av-Barclays Ctr (visit 2)

transfer lines

362 (12.1hrs): Atlantic Av-Barclays Ctr (visit 2)

363 (12.2hrs): Nevins St

364 (12.2hrs): Borough Hall

365 (12.2hrs): Nevins St (visit 2)

366 (12.2hrs): Hoyt St

367 (12.3hrs): Borough Hall

transfer lines

368 (12.3hrs): Court St

369 (12.4hrs): Jay St-MetroTech (visit 2)

transfer lines

370 (12.4hrs): Jay St-MetroTech (visit 2)

371 (12.4hrs): High St

372 (12.4hrs): Jay St-MetroTech (visit 3)

373 (12.5hrs): Hoyt-Schermerhorn Sts (visit 2)

374 (12.5hrs): Fulton St

375 (12.5hrs): Clinton-Washington Avs

376 (12.6hrs): Classon Av

377 (12.6hrs): Bedford-Nostrand Avs

378 (12.6hrs): Myrtle-Willoughby Avs

379 (12.6hrs): Flushing Av

380 (12.7hrs): Broadway

381 (12.7hrs): Metropolitan Av

382 (12.7hrs): Nassau Av

383 (12.8hrs): Greenpoint Av

384 (12.8hrs): 21 St

385 (12.8hrs): Court Sq

transfer lines

386 (12.9hrs): Court Sq

387 (12.9hrs): Hunters Point Av

388 (12.9hrs): Vernon Blvd-Jackson Av

389 (12.9hrs): Hunters Point Av (visit 2)

390 (13.0hrs): Court Sq (visit 2)

391 (13.0hrs): Queensboro Plaza

transfer lines

392 (13.0hrs): Queensboro Plaza

393 (13.0hrs): 39 Av-Dutch Kills

394 (13.1hrs): 36 Av

395 (13.1hrs): Broadway

396 (13.1hrs): 30 Av

397 (13.1hrs): Astoria Blvd

398 (13.2hrs): Astoria-Ditmars Blvd

399 (13.2hrs): Astoria Blvd (visit 2)

400 (13.2hrs): 30 Av (visit 2)

401 (13.2hrs): Broadway (visit 2)

402 (13.3hrs): 36 Av (visit 2)

403 (13.3hrs): 39 Av-Dutch Kills (visit 2)

404 (13.3hrs): Queensboro Plaza (visit 2)

transfer lines

405 (13.3hrs): Queensboro Plaza (visit 2)

406 (13.4hrs): 33 St-Rawson St

407 (13.4hrs): 40 St-Lowery St

408 (13.4hrs): 46 St-Bliss St

409 (13.4hrs): 52 St

410 (13.5hrs): 61 St-Woodside

411 (13.5hrs): 69 St

412 (13.5hrs): 74 St-Broadway

413 (13.5hrs): 82 St-Jackson Hts

414 (13.5hrs): 90 St-Elmhurst Av

415 (13.6hrs): Junction Blvd

416 (13.6hrs): 103 St-Corona Plaza

417 (13.6hrs): 111 St

418 (13.6hrs): Mets-Willets Point

419 (13.7hrs): Flushing-Main St

420 (13.8hrs): Mets-Willets Point (visit 2)

421 (13.8hrs): Junction Blvd (visit 2)

422 (13.9hrs): 74 St-Broadway (visit 2)

transfer lines

423 (13.9hrs): Jackson Hts-Roosevelt Av (visit 2)

424 (14.0hrs): Queens Plaza (visit 2)

425 (14.1hrs): Lexington Av/59 St

426 (14.2hrs): 5 Av/59 St

427 (14.2hrs): 57 St-7 Av

428 (14.3hrs): Lexington Av/63 St

429 (14.3hrs): 72 St

430 (14.3hrs): 86 St

431 (14.4hrs): 96 St

432 (14.4hrs): 86 St (visit 2)

433 (14.4hrs): 72 St (visit 2)

434 (14.5hrs): Lexington Av/63 St (visit 2)

435 (14.5hrs): Roosevelt Island

436 (14.6hrs): 21 St-Queensbridge

437 (14.6hrs): Roosevelt Island (visit 2)

438 (14.6hrs): Lexington Av/63 St (visit 3)

439 (14.7hrs): 57 St-7 Av (visit 2)

440 (14.7hrs): 49 St

441 (14.8hrs): Times Sq-42 St

transfer lines

442 (14.8hrs): Times Sq-42 St

transfer lines

443 (14.9hrs): Times Sq-42 St

444 (14.9hrs): Grand Central-42 St

transfer lines

445 (15.0hrs): Grand Central-42 St

446 (15.0hrs): 5 Av

447 (15.0hrs): Times Sq-42 St

448 (15.1hrs): 34 St-Hudson Yards

449 (15.1hrs): Times Sq-42 St (visit 2)

transfer lines

450 (15.2hrs): Times Sq-42 St (visit 2)

451 (15.2hrs): 34 St-Herald Sq

452 (15.2hrs): 28 St

453 (15.2hrs): 23 St

454 (15.3hrs): 14 St-Union Sq

455 (15.3hrs): 8 St-NYU

456 (15.3hrs): Prince St

457 (15.4hrs): Canal St

transfer lines

458 (15.4hrs): Canal St

459 (15.4hrs): City Hall

460 (15.5hrs): Cortlandt St

461 (15.5hrs): Rector St

462 (15.5hrs): Whitehall St-South Ferry

transfer lines

463 (15.6hrs): South Ferry Loop

transfer lines

464 (15.6hrs): Whitehall St-South Ferry (visit 2)

465 (15.7hrs): Court St (visit 2)

transfer lines

466 (15.7hrs): Borough Hall (visit 2)

467 (15.7hrs): Clark St

468 (15.8hrs): Wall St

469 (15.8hrs): Fulton St

470 (15.9hrs): Park Place

471 (15.9hrs): Chambers St

472 (15.9hrs): WTC Cortlandt

473 (15.9hrs): Rector St

474 (16.0hrs): South Ferry

475 (16.0hrs): Rector St (visit 2)

476 (16.0hrs): WTC Cortlandt (visit 2)

477 (16.0hrs): Chambers St (visit 2)

478 (16.1hrs): Franklin St

479 (16.1hrs): Canal St

480 (16.1hrs): Houston St

481 (16.1hrs): Christopher St-Sheridan Sq

482 (16.2hrs): 14 St

483 (16.2hrs): 18 St

484 (16.2hrs): 23 St

485 (16.2hrs): 28 St

486 (16.2hrs): 34 St-Penn Station

487 (16.3hrs): Times Sq-42 St (visit 2)

488 (16.3hrs): 50 St

489 (16.3hrs): 59 St-Columbus Circle (visit 2)

490 (16.3hrs): 66 St-Lincoln Center (visit 2)

491 (16.4hrs): 72 St (visit 2)

492 (16.4hrs): 79 St

493 (16.4hrs): 86 St

494 (16.4hrs): 96 St (visit 2)

495 (16.5hrs): 103 St

496 (16.5hrs): Cathedral Pkwy (110 St)

497 (16.5hrs): 116 St-Columbia University

498 (16.5hrs): 125 St

499 (16.6hrs): 137 St-City College

500 (16.6hrs): 145 St

501 (16.6hrs): 157 St

502 (16.7hrs): 168 St-Washington Hts

503 (16.7hrs): 181 St

504 (16.7hrs): 191 St

505 (16.7hrs): Dyckman St

506 (16.8hrs): 207 St

507 (16.8hrs): 215 St

508 (16.8hrs): Marble Hill-225 St

509 (16.8hrs): 231 St

510 (16.9hrs): 238 St

511 (16.9hrs): Van Cortlandt Park-242 St

512 (16.9hrs): 238 St (visit 2)

513 (17.0hrs): 231 St (visit 2)

514 (17.0hrs): Marble Hill-225 St (visit 2)

515 (17.0hrs): 215 St (visit 2)

516 (17.0hrs): 207 St (visit 2)

517 (17.1hrs): Dyckman St (visit 2)

518 (17.1hrs): 191 St (visit 2)

519 (17.1hrs): 181 St (visit 2)

520 (17.1hrs): 168 St-Washington Hts (visit 2)

transfer lines

521 (17.2hrs): 168 St

522 (17.3hrs): 175 St

523 (17.3hrs): 181 St

524 (17.3hrs): 190 St

525 (17.4hrs): Dyckman St

526 (17.4hrs): Inwood-207 St

527 (17.5hrs): Dyckman St (visit 2)

528 (17.5hrs): 190 St (visit 2)

529 (17.5hrs): 181 St (visit 2)

530 (17.5hrs): 175 St (visit 2)

531 (17.6hrs): 168 St (visit 2)

532 (17.6hrs): 163 St-Amsterdam Av

533 (17.6hrs): 155 St

534 (17.6hrs): 145 St

535 (17.7hrs): 135 St

536 (17.7hrs): 145 St

537 (17.8hrs): Tremont Av

538 (17.9hrs): Fordham Rd

539 (17.9hrs): Kingsbridge Rd

540 (18.0hrs): Bedford Park Blvd

541 (18.0hrs): Norwood-205 St

542 (18.0hrs): Bedford Park Blvd (visit 2)

543 (18.1hrs): Kingsbridge Rd (visit 2)

544 (18.1hrs): Fordham Rd (visit 2)

545 (18.2hrs): 182-183 Sts

546 (18.2hrs): Tremont Av (visit 2)

547 (18.2hrs): 174-175 Sts

548 (18.2hrs): 170 St

549 (18.3hrs): 167 St

550 (18.3hrs): 161 St-Yankee Stadium

transfer lines

551 (18.4hrs): 161 St-Yankee Stadium

552 (18.4hrs): 167 St

553 (18.4hrs): 170 St

554 (18.4hrs): Mt Eden Av

555 (18.5hrs): 176 St

556 (18.5hrs): Burnside Av

557 (18.5hrs): 183 St

558 (18.5hrs): Fordham Rd

559 (18.6hrs): Kingsbridge Rd

560 (18.6hrs): Bedford Park Blvd-Lehman College

561 (18.6hrs): Mosholu Pkwy

562 (18.7hrs): Woodlawn

563 (18.7hrs): Mosholu Pkwy (visit 2)

564 (18.7hrs): Bedford Park Blvd-Lehman College (visit 2)

565 (18.8hrs): Kingsbridge Rd (visit 2)

566 (18.8hrs): Fordham Rd (visit 2)

567 (18.8hrs): 183 St (visit 2)

568 (18.8hrs): Burnside Av (visit 2)

569 (18.9hrs): 167 St (visit 2)

570 (19.0hrs): 161 St-Yankee Stadium (visit 2)

transfer lines

571 (19.0hrs): 161 St-Yankee Stadium (visit 2)

572 (19.0hrs): 155 St

573 (19.1hrs): 145 St (visit 2)

574 (19.1hrs): 125 St

575 (19.1hrs): 116 St

576 (19.2hrs): Cathedral Pkwy (110 St)

577 (19.2hrs): 103 St

578 (19.2hrs): 96 St

579 (19.2hrs): 86 St

580 (19.3hrs): 81 St-Museum of Natural History

581 (19.3hrs): 72 St

582 (19.3hrs): 59 St-Columbus Circle (visit 2)

583 (19.3hrs): 42 St-Port Authority Bus Terminal (visit 2)

584 (19.4hrs): 34 St-Penn Station (visit 2)

585 (19.4hrs): 14 St (visit 2)

transfer lines

586 (19.4hrs): 8 Av

587 (19.5hrs): 6 Av

588 (19.5hrs): 14 St-Union Sq

589 (19.5hrs): 3 Av

590 (19.5hrs): 1 Av

591 (19.6hrs): Bedford Av

592 (19.6hrs): Lorimer St

593 (19.6hrs): Graham Av

594 (19.7hrs): Grand St

595 (19.7hrs): Montrose Av

596 (19.7hrs): Morgan Av

597 (19.7hrs): Jefferson St

598 (19.8hrs): DeKalb Av

599 (19.8hrs): Myrtle-Wyckoff Avs

600 (19.8hrs): Halsey St

601 (19.9hrs): Wilson Av

602 (19.9hrs): Bushwick Av-Aberdeen St

603 (19.9hrs): Broadway Junction (visit 2)

604 (19.9hrs): Bushwick Av-Aberdeen St (visit 2)

605 (20.0hrs): Wilson Av (visit 2)

606 (20.0hrs): Halsey St (visit 2)

607 (20.0hrs): Myrtle-Wyckoff Avs (visit 2)

transfer lines

608 (20.1hrs): Myrtle-Wyckoff Avs

609 (20.1hrs): Seneca Av

610 (20.1hrs): Forest Av

611 (20.2hrs): Fresh Pond Rd

612 (20.2hrs): Middle Village-Metropolitan Av

613 (20.2hrs): Fresh Pond Rd (visit 2)

614 (20.3hrs): Forest Av (visit 2)

615 (20.3hrs): Seneca Av (visit 2)

616 (20.3hrs): Myrtle-Wyckoff Avs (visit 2)

617 (20.3hrs): Knickerbocker Av

618 (20.4hrs): Central Av

619 (20.4hrs): Myrtle Av

620 (20.5hrs): Marcy Av

621 (20.5hrs): Hewes St

622 (20.5hrs): Lorimer St

623 (20.6hrs): Flushing Av

624 (20.6hrs): Myrtle Av (visit 2)

625 (20.6hrs): Kosciuszko St

626 (20.6hrs): Gates Av

627 (20.7hrs): Halsey St

628 (20.7hrs): Chauncey St

629 (20.7hrs): Broadway Junction (visit 2)

Detecting code copying at scale with Vendetect

a new tool that can discover coded copied between repositories

Earlier this month, the maintainer of Cheating-Daddy discovered that a Y-Combinator-funded startup had copied their GPL-licensed codebase, stripped out the comments, and re-released it as “Glass” under an incompatible license. This isn’t an isolated incident; we see code theft and improper vendoring constantly during security assessments. So we built a tool to catch it automatically.

Vendetect is our new open-source tool for detecting copied and vendored code between repositories. It uses semantic fingerprinting to identify similar code even when variable names change or comments disappear. More importantly, unlike academic plagiarism detectors, it understands version control history, helping you trace vendored code back to its exact source commit.

Investigate your dependencies with Deptective

a new tool that can automatically run any command even if its dependencies are missing

Have you ever tried compiling a piece of open-source software, only to discover that you neglected to install one of its native dependencies? Or maybe a binary “fell off the back of a truck” and you want to try running it but have no idea what shared libraries it needs. Or maybe you need to use a poorly packaged piece of software whose maintainers neglected to list a native dependency.

Deptective, our new open-source tool, solves these problems. You can give it any program, script, or command, and it will find a set of packages sufficient to run the software successfully.

This blog post highlights key points from our new white paper Preventing Account Takeovers on Centralized Cryptocurrency Exchanges, which documents ATO-related attack vectors and defenses tailored to CEXes.

Imagine trying to log in to your centralized cryptocurrency exchange (CEX) account and your password and username just… don’t work. You try them again. Same problem. Your heart rate increases a little bit at this point, especially since you are using a password manager. Maybe a service outage is all that’s responsible (knock on wood), and your password will work again as soon as it’s fixed? But it is becoming increasingly likely that you’re the victim of an account takeover (ATO).

CEXes’ choices dictate how (or if) the people who use them can secure their funds. Since account security features vary between platforms and are not always documented, the user might not know what to expect nor how to configure their account best for their personal threat model. Design choices like not supporting phishing-resistant multifactor authentication (MFA) methods like U2F hardware security keys, or not tracking user events in order to push in-app “was this you?” account lockdown prompts when anomalies happen invite the attacker in.

Our white paper’s goal is to inform and enable CEXes to provide a secure-by-design platform for their users. Executives can get a high-level overview of the vulnerabilities and entities involved in user account takeover. We recommend a set of overlapping security controls that they can bring to team leads and technical product managers to check for and prioritize if not yet implemented. Security engineers and software engineers can also use our work as a reference for the risks of not integrating, maintaining, and documenting appropriate ATO mitigations.

I grew up on the fringes of suburbia, at the cusp of what most would consider rural Pennsylvania. In the Spring, we gagged from the stench of manure. In the Fall, Schools closed on the first day of hunting season. In the Winter, fresh, out-of-season fruits were missing from the grocer. All year round, procuring exotic ingredients like avocados entailed a forty-five-minute drive toward civilization. During the school year, I was the first to be picked up and last to be dropped off by the bus, enduring a ride that was well over an hour each way.

I also grew up in tandem with the burgeoning cruise line industry. My parents quickly adopted that mode of travel, and it eventually became our sole form of vacation. As a kid, it was great: I had the freedom to roam the decks on my own, there were innumerable activities, and an unlimited supply of delicious foods with exotic names like “Consommé Madrilene” and “Contrefilet of Prime Beef Périgueux”. My parents loved it because it kept their kids busy, was very affordable (relative to equivalent landed resorts), and had sufficient calories to satisfy their growing boy’s voracious appetite. This was also a transitional period when cruises were holding onto the vestiges and traditions of luxury ocean liners. All cruise lines had strict dress codes, requiring formal attire some evenings (people brought tuxedos!). The crew were largely Southern and Eastern European. As a kid who had never traveled outside North America, it felt like I was LARPing as James Bond.

When I moved out of my parents’ house for college, I wanted a change of scenery. While I had the option to move to a “college town”, I instead chose to live in a large city. And I loved it. It was like living on a cruise, all year round: Activities galore, amazing food, and all within a short distance of each other. A friend could call me up and say, ”Hey, we are hanging out at [X], would you like to join us?” And, regardless of where X was in the city, I could meet them there within fifteen minutes either by walking, biking, or taking public transport.

I didn’t need cruises anymore.

Preface

This year, for his birthday, my father only had one request: that he and his extended family take a cruise to celebrate. I just returned from that cruise, and it was a very different experience from the ones of my youth.

As an adult who had by this point lived the majority of his life in large cities, all I wanted to do was lay by a pool or, preferably, the beach all day and read a book. Those are both difficult things when you’re sharing a crowded pool space with over six thousand other people, and the ship doesn’t typically dock close to a good beach. Skating rink? Gimmicky specialty restaurants? Luxury shopping spree? Laser tag? Pub trivia? Theater productions? Comedy shows? I can do all of those things any day of the week a short distance from my house. When I vacation, I want to escape all that freneticism.

My wife, kids, and I were the only urbanites in our group, and my parents didn’t seem to comprehend why we had such little interest in all the activities. And then it dawned on me: A cruise is just a simulated city. Why would I want an artificial version of what I already have?

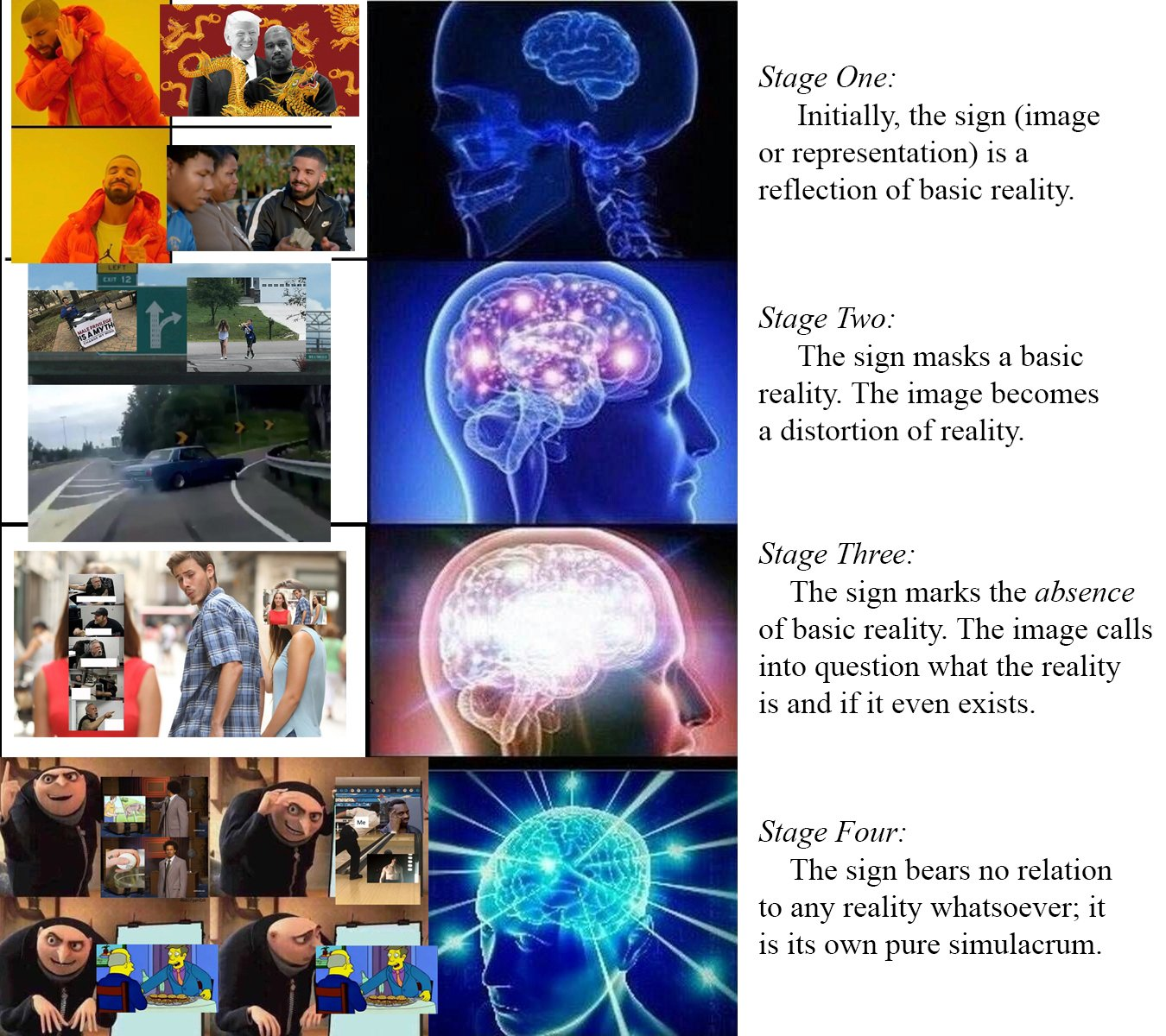

So, lying down on a deck chair, instead of reading my book, I started writing. The idea of simulated urbanism isn’t new, but it’s typically discussed in terms of curated amusement parks like Disney and the emergence of suburban “lifestyle center” developments. Therefore, initially, my goal was to channel this insight into as obnoxious a treatise as possible, in order to trigger my suburbanite traveling companions. Simulated urbanism? That reminded me of Baudrillard! I would make it a completely over-the-top academic analysis of the topic.

The following was compiled from a series of texts I sent to our group chat throughout the cruise.

Abstract

This article explores the paradox of vacation preferences among suburban Americans who gravitate toward densely populated environments such as cruises, European cities, and amusement parks, despite residing in sparsely populated areas. It examines how cruises and lifestyle centers, which mimic urban density while offering suburban convenience, satisfy the suburban desire for urban-like experiences. The article contrasts these preferences with those of urban Americans, who experience density daily and may seek different vacation experiences. By analyzing the dynamics of suburban and urban vacation choices, we highlight the complex interplay between suburban living and the pursuit of urban escapism.

Simulated Urbanism

Simulacra and Simulation

The concept of ”simulated urbanism,” as seen in cruise ships and lifestyle centers, can be analyzed through the lens of Jean Baudrillard’s philosophy, particularly his ideas on simulation and hyperreality. Baudrillard argues that in contemporary society, simulations—representations or imitations of reality—have become so pervasive that they blur the distinction between what is real and what is artificially constructed. In the context of simulated urbanism, lifestyle centers and cruise ships serve as hyperreal environments that imitate the vibrancy and density of urban life without the complexities and inconveniences associated with real urban spaces. They provide an experience that is more accessible, manageable, and, in some ways, more appealing than the genuine urban environments they emulate. According to Baudrillard, these simulations can create a sense of hyperreality, where the imitation becomes more influential or desirable than reality itself. Suburban Americans, who are accustomed to the sprawling, car-dependent landscapes of suburbia, find in these simulated urban environments a curated and sanitized version of city life. This artificial urbanism allows them to engage with the aesthetics and experiences of urban density—such as walkability, diverse entertainment, and social interaction—without the perceived drawbacks of real urban living, like congestion, pollution, and crime. Thus, simulated urbanism not only fulfills a desire for the excitement and dynamism of city life but also constructs a hyperreal experience that is tailored to the preferences and comfort of suburban consumers, aligning with Baudrillard’s notion of a society increasingly detached from the authenticity of the real world.Metamodernism

Suburbanites’ predilections for cruising can be interpreted through the theoretical framework of metamodernism, which posits an oscillation between opposing cultural and experiential paradigms. The cruise experience encapsulates a synthesis of modernist aspirations for progress, order, and structured entertainment, alongside a postmodern sensibility characterized by irony and skepticism towards mass consumerism and the spectacle. This dialectical tension aligns with metamodernism’s core principle of navigating and reconciling contradictions. Within the confines of a cruise, suburbanites engage with the modernist ideal of escape and luxury, encountering a curated simulacrum that offers both adventure and novelty. Simultaneously, they remain cognizant of the inherent artifice and commodification intrinsic to the cruise experience, reflecting a postmodern consciousness of the limitations and constructed nature of such escapism.

Furthermore, the pragmatic idealism inherent in metamodernism is evident in the suburban pursuit of cruising, representing a quest for authenticity within a meticulously orchestrated environment. Suburbanites partake in cruising as a form of meaningful escapism that, although commodified, facilitates genuine opportunities for relaxation, social interaction, and cultural exploration. This dynamic reflects a metamodern synthesis of sincerity and irony, wherein participants seek genuine engagement and fulfillment while maintaining an awareness of the artificial and consumerist underpinnings of the cruise industry. The cruise, thus, serves as a microcosm of metamodern cultural hybridity, integrating diverse influences and experiences into a cohesive assemblage that enables suburbanites to navigate the complexities of contemporary existence with both optimism and reflexivity. This exemplifies the metamodern tension between the yearning for authentic connection and the recognition of its mediated nature, embodying a dialectical interplay that is central to metamodern thought.

Dialectics

(To be read as if dictated by Slavoj Žižek.)

From a Hegelian perspective, urbanites’ preferences for relaxing vacations can be understood through the lens of dialectical progression and the quest for synthesis between opposing elements in their lives. Hegel’s philosophy emphasizes the process of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, [sniff] where the contradictions and tensions between different aspects of existence lead to the development of higher levels of understanding and being. A dance of contradictions and tensions.

Urbanites are like rats in a maze of their own making, living in this frenetic environment of constant stimulation and complexity. So, what do they do? They escape to a vacation that provides the antithesis of urban life, a necessary counterbalance that allows them to confront the contradictions of their daily existence.

In this dialectical process, the vacation can be seen as a moment of synthesis, where urbanites integrate the contrasting aspects of their existence—work and leisure, complexity and simplicity, stimulation and relaxation. Through this synthesis, they achieve a more harmonious state of being, temporarily resolving the contradictions inherent in their lives. [nose pull] Hegel might argue that this pursuit of balance is part of a broader process of self-realization and development, as individuals continually seek to reconcile opposing forces within themselves and their environments. This dialectical movement reflects a deeper philosophical journey toward self-awareness and fulfillment, where each vacation experience contributes to a more nuanced understanding of personal and existential needs.

Moreover, Hegel would likely emphasize that this process is not static but dynamic, as urbanites constantly redefine and re-evaluate their desires and experiences in pursuit of higher forms of understanding and contentment. [sniff] This ongoing dialectical interaction between urban life and vacation preferences underscores the complexity of human existence and the continuous evolution of individual consciousness within the broader historical and cultural context.

What Would Marx Say?

(For extra fun, to be read as if dictated by Jordan Peterson.)

When we examine the suburbanite’s preference for urban-like vacation experiences—such as cruising or visiting bustling cities—through the lens of Marxist theory, we uncover something quite profound about the alienation inherent in capitalist societies. Suburban life is often marked by routine and compartmentalization, a strong reliance on cars, and an emphasis on private space. This creates an environment of isolation and fragmentation, which Marx identified as symptomatic of capitalist production. The sprawling nature of suburbia physically separates individuals from their workplaces, social hubs, and cultural activities, generating a dichotomy between home life and community engagement. This alienation from collective social experiences mirrors the detachment workers feel from the products of their labor and from each other in a capitalist framework.

Thus, when suburbanites seek out vacations in dense, walkable environments, they’re searching for a temporary reprieve from this isolation. These vacations allow them to engage with the social interactions and cultural experiences that are often missing from their everyday lives. In this way, vacations become a commodified form of leisure within capitalist society, packaged and sold as products designed to alleviate the stresses of alienation and labor. Suburbanites, who feel the pressures of maintaining a lifestyle dictated by capitalist norms—like homeownership and consumerism—turn to vacations as a form of respite from these demands. Cruises and urban vacations offer a concentrated form of entertainment and cultural engagement, providing an illusion of freedom and choice that contrasts with the regulated and constrained nature of suburban life. While these vacations temporarily satisfy the need for genuine human connection and cultural enrichment, Marxist theory would argue that they also reinforce the capitalist cycle, as individuals must return to their suburban routines to earn the means to participate in such leisure activities. Thus, vacations, though they offer a brief escape from alienation, ultimately underscore the pervasive influence of capitalism on leisure and personal fulfillment.

Conclusions

As I reflect on the whirlwind of contradictions, philosophies, and cultural dynamics explored in this article, I must admit that I find myself utterly exhausted. Much like the aftermath of a cruise, where the buffet line feels both endless and insurmountable, I am too fatigued to draw any tidy conclusions. So, dear reader, as I lean back in my metaphorical deck chair, I invite you to navigate these intellectual waters and draw your own conclusions. Like the towel animals on your cabin bed, reality might be folded and shaped in surprising ways, but the essence remains yours to unravel. Bon voyage in your own journey of trolling! Or is it trawling?

How to avoid the aCropalypse

It could have been prevented if only Google and Microsoft used our tools!

Last week, news about CVE-2023-21036, nicknamed the “aCropalypse,” spread across Twitter and other media, and my colleague Henrik Brodin quickly realized that the underlying flaw could be detected by our tool, PolyTracker. Coincidentally, Henrik Brodin, Marek Surovič, and I wrote a paper that describes this class of bugs, defines a novel approach for detecting them, and introduces our implementation and tooling. It will appear at this year’s workshop on Language-Theoretic Security (LangSec) at the IEEE Security and Privacy Symposium.

The remainder of this blog post describes the bug and how it could have been detected or even prevented using our tools.

A couple of years ago I released PolyFile: a utility to identify and map the semantic structure of files, including polyglots, chimeras, and schizophrenic files. It’s a bit like file, binwalk, and Kaitai Struct all rolled into one. PolyFile initially used the TRiD definition database for file identification. However, this database was both too slow and prone to misclassification, so we decided to switch to libmagic, the ubiquitous library behind the file command.

PoC‖GTFO

PoC‖GTFO Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn GitHub

GitHub XTerm

XTerm

Esperanto

Esperanto

עברית

עברית

Medžuslovjansky

Medžuslovjansky

Русский

Русский

This is an excerpt from the

This is an excerpt from the